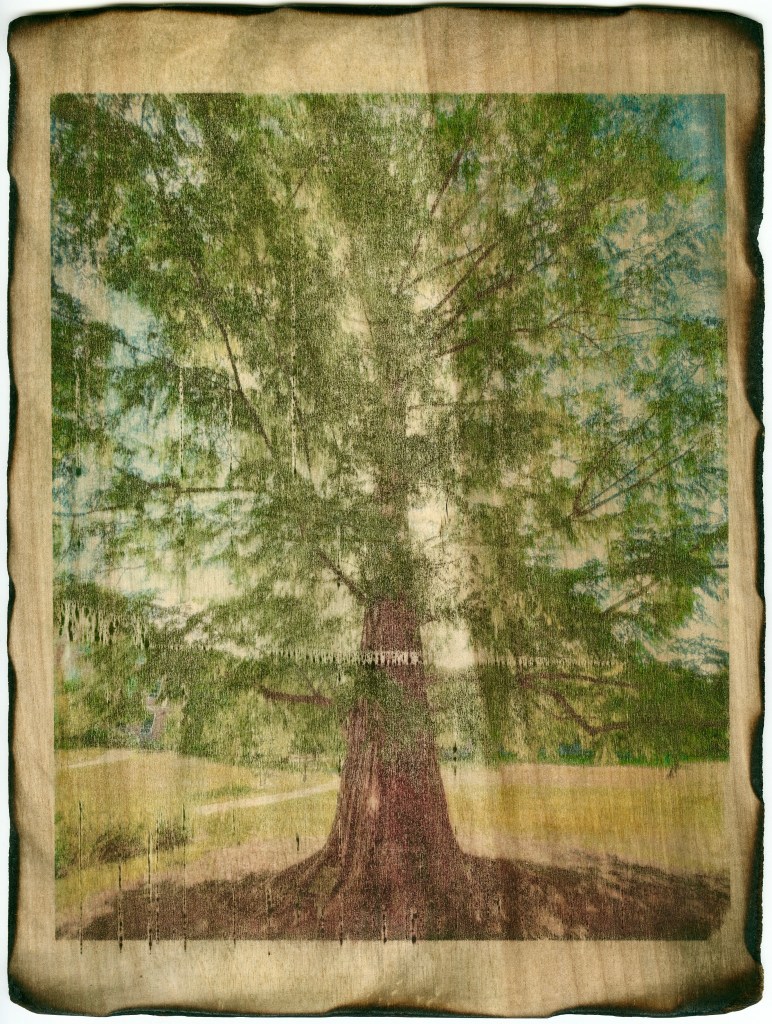

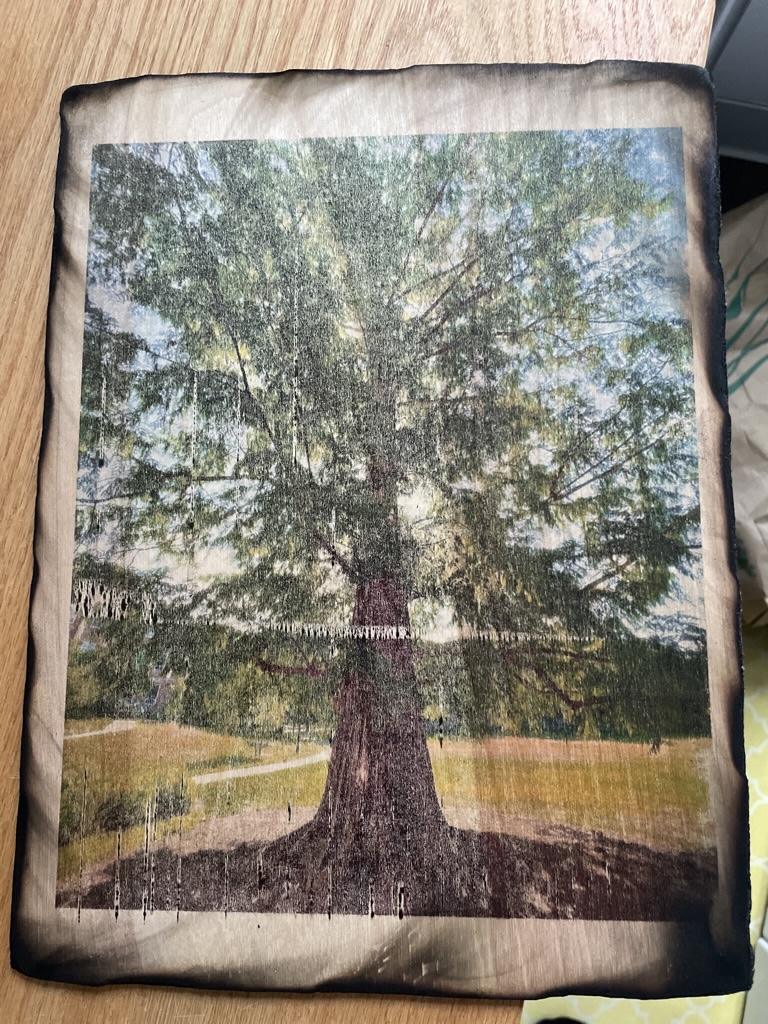

Portrait of a Dawn Redwood at the End of the Anthropocene

2022

9×12″ Ink, pond cypress varnish, fire, wood board

This piece emerged from an extended reckoning with climate change and personal loss. As a tree ecophysiologist, I come face to face with the realities of forests dealing with extreme drought conditions. I chose to work in wood, tree resin, and fire to make tangible the subject of tree mortality.

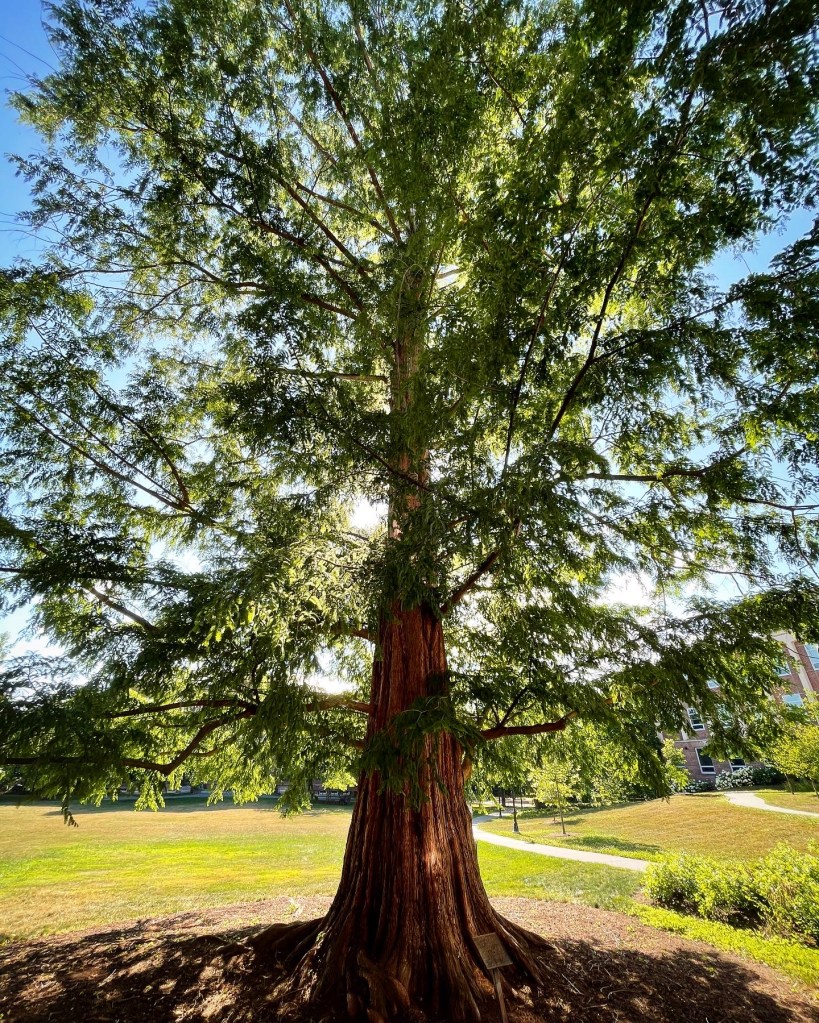

The dawn redwood (Metasequoia glyptostroboides) was believed extinct for 150 million years until living specimens were discovered in China in the 1940s. The Smith College dawn redwood, planted from those original seeds in 1948, is a beloved presence on campus—its buttressed form and towering height set it apart from the surrounding canopy. I fell in love with this tree years before becoming a student, captivated by the chance to meet a redwood in person. One summer evening I photographed it as the sun set behind its branches, light streaming through the feathered needles.

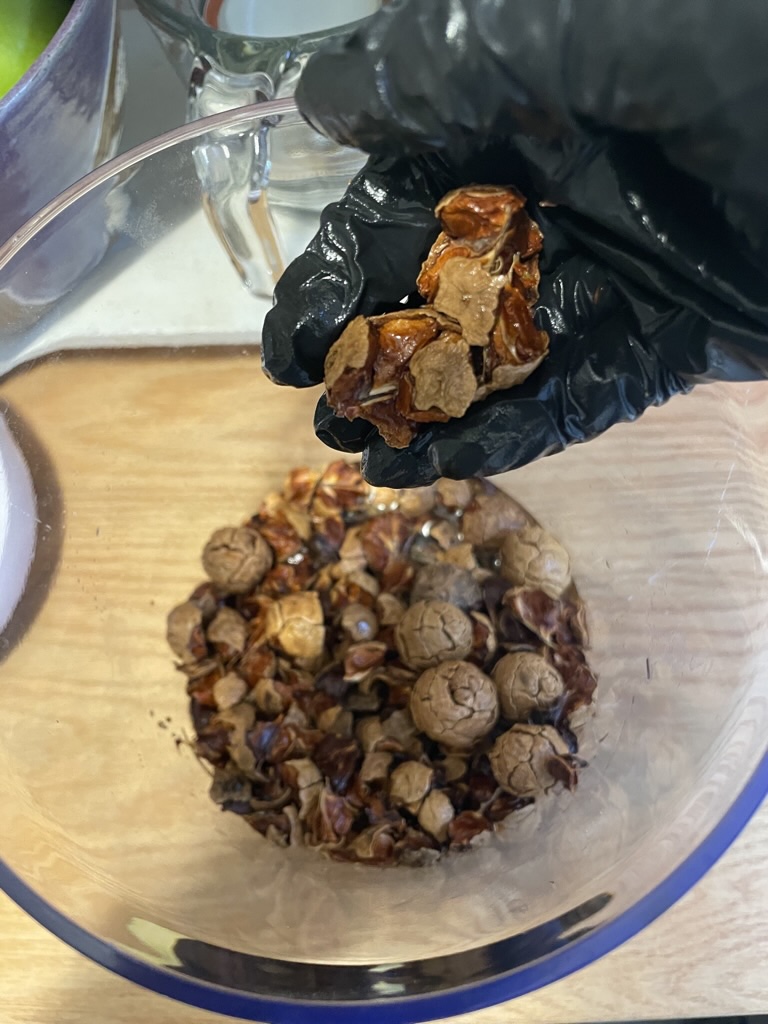

The process began unexpectedly. While cleaning seeds from a pond cypress (Taxodium distichum) at the Smith College Botanic Garden, I noticed each seed carried a small cocoon of resin. As I handled them, the packets burst open, coating my hands in rich, amber-colored substance. I was transfixed by its slow adherence to everything it touched, and I began thinking about the chemistry of resins—the way trees produce them as protection. I wanted to bring this material into my work.

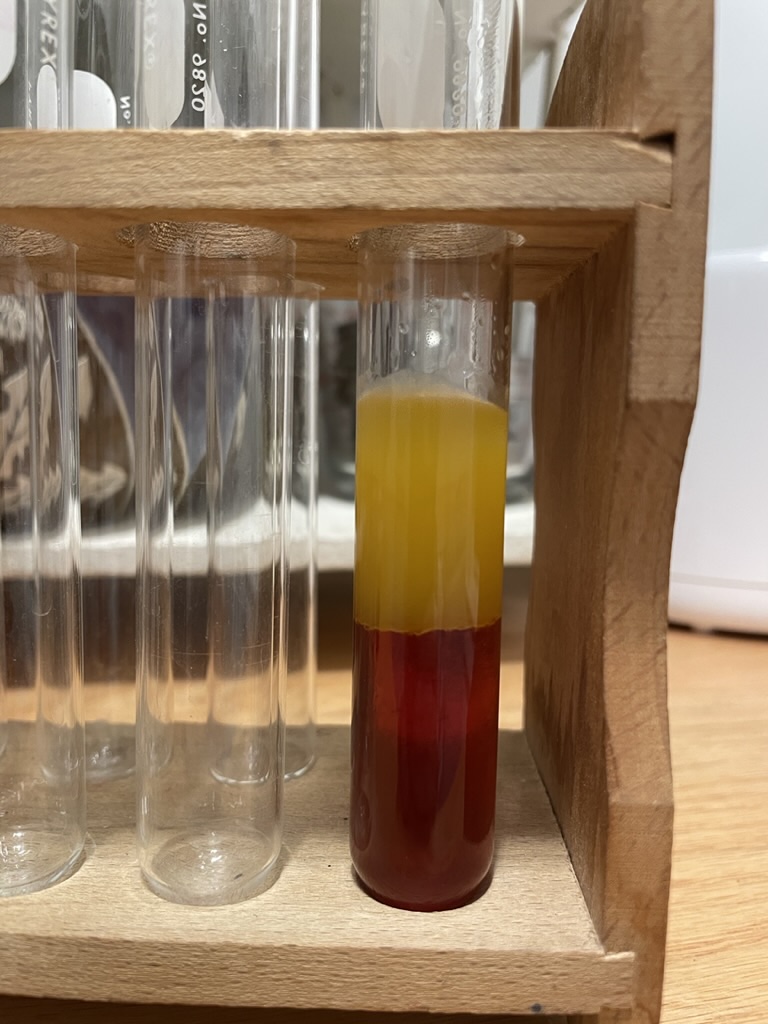

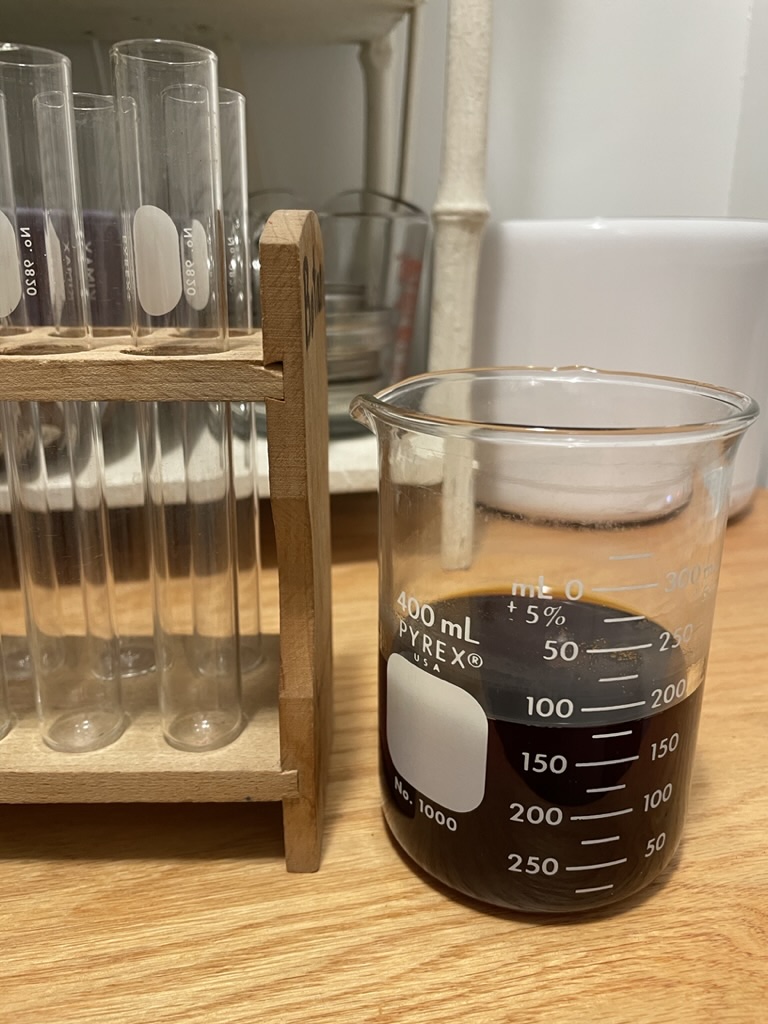

Researching the history of resin use, I found extensive documentation: pine tar, incense, amber, waterproofing, antimicrobial medicines, adhesives, sealants. Tree resin has been essential to human life across cultures and millennia. To incorporate it into this piece, I developed my own varnish. Resin molecules are nonpolar, making them insoluble in water—which is precisely why they seal so effectively. Since like dissolves like, I used isopropyl alcohol as a solvent. I poured it into a container with the seed cones and shook. The liquid turned golden brown within minutes. I filtered it through cheesecloth, then added lavender oil—a technique borrowed from colloidal wet-plate photography. Meanwhile, I transferred my photograph onto wood by printing ink onto wax paper, laying it face down, and rubbing until the image embedded in the grain.

I burned the edges of the wood with fire—a reference to wildfire and controlled burning. Late at night, standing over the sink with a lighter and an exhaust fan in the window, I lit the edges and blew them out, a few inches at a time. The controlled slow burn was necessary: I needed to burn away splinters and smooth the perimeter without letting the whole thing ignite.

The wood turned black with glowing embers. Smoke pulled through the fan and out into the cold night. I thought of carbon extracted from the earth and burned for fuel. I thought of the Carboniferous period—how lush it must have been, massive ferns and mosses and cycads achieving the form of trees in thick humid air. Heat works quickly. It took ice hundreds of millions of years to press those ancient plants into coal. It takes a second or two for coal to combust. I ran my finger over the burned edge and it came away black.

When I applied the varnish, I did not know if it would dissolve the ink or function at all. I rubbed small amounts into the corners, and it seemed to soothe the charred wood. The varnish sank into the grain, turning it gold and shimmery. It smelled of lavender and cypress, sharp with alcohol. I poured the honey-like mixture over the image of the dawn redwood and gently worked it across the surface. Some ink lifted, but more varnish absorbed. The wood drank it in. I massaged it into the burnt edges until there was no more crumbling soot. The whole piece glistened, the grain now visible through the image—mimicking the way light had shone through the branches of the living tree. The next morning I applied a second coat to deepen color and shine.

In the same way that the pond cypress held resin in its cones to protect its seeds, the resin now protects a portrait of the dawn redwood. The trees go on through the seasons as we go on through our days, the atmosphere filling with carbon dioxide, the earth’s cycles tilting off balance. We will do our best science as the loss accumulates. On the scale of the earth, millions of years pass and life persists. On the scale of a human, how lucky it is to be friends with a tree.